When my office received our initial shipment of influenza vaccine in 2018, we wanted to provide immunizations to our most vulnerable patients quickly. But how could we find them out of the thousands who regularly look to us for care? Earlier in the year, through a process known as risk stratification, we had evaluated our entire patient panel and assigned a risk level to each one. We immediately assigned staff to reach out to our highest risk patients to ensure that they received the vaccine.

In family medicine, we manage patients with conditions that vary widely in their medical complexity. Each requires a different amount of resources, depending on that complexity. An otherwise healthy patient with a viral upper respiratory tract infection needs a short office visit and no referrals, while a patient receiving end-of-life care requires extra previsit planning, additional in-office time, referrals to specialists or home care providers, and an extended follow-up plan.

Risk stratification is a technique for systematically categorizing patients based on their health status and other factors. It allows for risk-stratified care management, in which practices manage patients based on their assigned risk level to make better use of limited resources, anticipate needs, and more proactively manage their patient population. (See “From risk stratification to risk-stratified care management.”)

This article will explain how our practice uses a structured, algorithmic approach to determine our patients' risk levels and drive better care team support for our patients.

Risk stratification has enabled our practice to provide risk-stratified care management. Here are some examples.

For the purpose described in this article, “risk” refers to clinical risk, or the likelihood of an adverse clinical outcome. Sometimes clinical risk is obvious; for example, you would expect a patient with rheumatoid arthritis to have more complications in the future than a patient with osteoarthritis. Other times, risk assessment comes down to your “gut feeling” about what's going on with the patient.

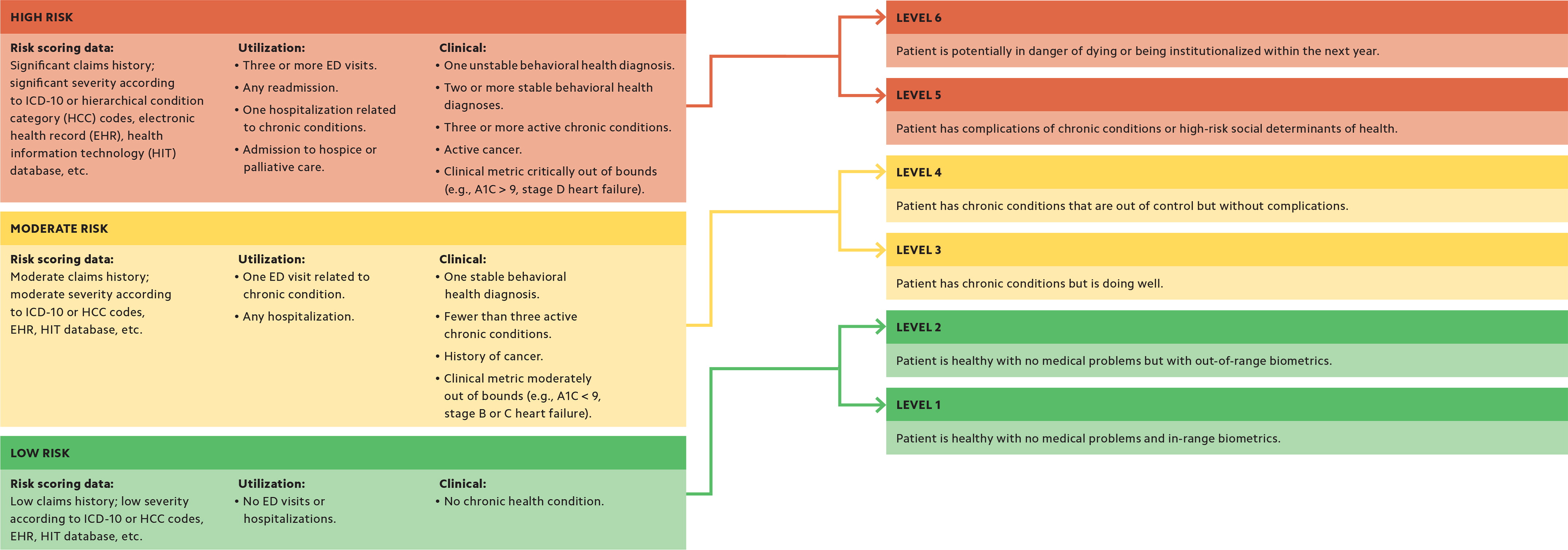

Our practice uses a two-step algorithm to determine a patient's risk level based on objective data and subjective clues. (See “Risk-stratification algorithm.”) This approach is loosely based on the American Academy of Family Physicians' Risk-Stratified Care Management Rubric).

Step one involves sorting patients into one of three risk groups (high, medium, and low) based on objective data, which we take from claims or our electronic health record (EHR). We make our determinations based on the presence or absence of such factors as chronic conditions, advanced age, multiple comorbidities, physical limitations, substance abuse, a lack of health insurance, low health literacy, frequent hospitalizations or emergency department (ED) visits, recent major surgery or brain trauma, polypharmacy, or difficulty following a treatment plan. Some EHRs will calculate a risk score automatically based on this data. In either case, it is important to adjust the score based on additional, subjective considerations, which are the focus of step two.

In step two we assign each patient to one of six risk levels based on how physicians and staff answer the following questions:

We have found that combining objective data and subjective input allows us to better assess a patient's risk level. For example, a patient with diabetes whose A1C is 9.2 could be categorized as high risk. However, consider that the patient had an A1C of 12 earlier in the year but has since begun exercising, lost 30 pounds, and started taking his or her medication as prescribed. This subjective data leads us to assign the patient a lower risk level. We also consider several additional factors that we refer to as “Escalation/de-escalation criteria” to fine-tune the final risk score.

These intangible factors can lead staff to increase or decrease a patient's step-two risk level:

There are several ways to implement risk stratification in your practice workflow, depending on your staffing, patient population, and goals. A smaller practice with fewer resources might want to focus on just a subset of patients, while a larger practice might want to risk stratify the entire patient population. Here are a few ways to get started:

Whatever method you use, risk stratification should be seen as a dynamic process. You should reevaluate risk scores regularly and also as you become aware of changes in the patient's status. For example, an ED admission, a care-gap report from a payer, or a chance encounter with a patient at your child's baseball game could prompt you to change a risk score.

Of course, the purpose of risk stratification is not to simply assign a risk score but to gain a fuller, more integrated view of patients and manage them accordingly. We make each patient's risk level readily available to physicians and staff as a global alert in our EHR. You may be able to do something similar with your system. Everything we do for patients — access, referrals, care planning, etc. — is filtered through the lens of their risk score. For example, we schedule longer visits with patients who have higher levels of risk — 30 minutes for level-5 and level-6 patients when we see them for chronic disease management. Patients with lower risk levels are scheduled for 20-minute visits. If your practice has a care manager, you could strategically deploy that manager to the highest-risk patients. Risk levels could also be used to identify patients who would benefit from additional services, such as group visits, disease education classes, referral tracking, or additional follow up. (See “Comparison of risk-stratified care management at different risk levels.”)

Risk stratifying an entire patient panel can be time- and resource-intensive, at least initially. It's a lot like learning how to read an electrocardiogram (EKG): at first, the process is difficult, but with practice you eventually can read most EKGs in seconds. We risk stratified more than 4,700 patients who came into our office over the course of a year.

It may take some extra time, but it is important to incorporate the care team's perception of risk. The practice must be committed to a team-based approach that values the input of nonphysicians and a commitment to developing and adhering to structured workflows and processes.

This may be a new way of thinking for some practices, and not all are ready for it. Smaller practices typically can accommodate changes like these more nimbly than larger practices because smaller practices may have fewer administrative barriers to overcome. (See “Tips for successful risk stratification.”)

Risk stratification has shown clear benefits in our practice. As part of the Comprehensive Primary Care Plus program, we get detailed utilization data on enrolled patients. Between the second quarter of 2017, when we began risk stratification, and the third quarter of 2018, overall Medicare spending on those patients decreased almost 23 percent and their ED utilization fell 19 percent.

Other risk-stratification models, such as the John's Hopkins Adjusted Clinical Groups Model, have also shown the ability to predict utilization, 2 although many of these models only use diagnosis codes or other objective information. More recent studies suggest that including subjective data increases the chance of identifying higher-risk patients and connecting them with additional resources. 3

Two-step risk stratification that sorts patients into high-, moderate-, and lower-risk groups based on their potential for clinical complications is not simple or quick. It requires readily available objective data and physicians and other providers who truly understand their patients and their individual conditions. But risk scores allow practices to better manage their patients and more efficiently use the resources available.